Ideensammlung

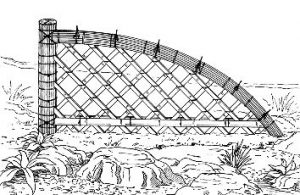

Raumteiler

Photogalerie

Pflanzen

Verschiedene Pflanzen, welche in einen japanischen Garten passen würden.

- Schmuck-Farn

- Azalee

- Päonie

- Sternmoos

Wasser

Trokenanlage

Mizubashi

Steine

Stones—large and small—are a major component of most Japanese gardens, and must have been important from the very beginnings of garden design. As Takei’s and Keane’s recent translation of the Sakuteiki points out, the opening line of that oldest of Japanese garden manuals equates the creation of gardens with the setting of stones. The “meaning” and the aesthetic appeal of garden stones have been the subjects of much analysis by the students of these gardens, but it is a controversial topic. There can be little doubt that the use of stones and the reverence shown them have roots in Shinto belief, but the exact nature of stone worship in prehistoric Japan can only be surmised. That the selection and placing of stones in the historic period has a spiritual component cannot be denied, however, as that responsibility often fell to the priestly caste. The Sakuteiki specifically mentions the secrets of rock-placing and associates them with the priest En no Enjari. Indeed, stones and the placing of stones are the major concern in garden design according to that ancient text, particularly since the poor placement of stones would lead to misfortune and illness.

In the Muromachi Period, the task of selecting and placing stones sometimes fell to members of the kawaramono, or “river-bed people,” a group of outcasts living along the riverbanks of Kyoto’s Kamo River. In at least one instance, a kawaramono became not only a garden designer but also a general advisor to the shogun in matters of aesthetics (Zen’ami, 1386-1482). The garden of Ginkaku-ji, represented on this page, has been attributed to him.

Interesting enough, also here we have a link to the Sakuteiki.